Forge & Fire: 5 Shocking Truths About a Medieval Blacksmith's Day!

Forge & Fire: 5 Shocking Truths About a Medieval Blacksmith's Day!

Ever wondered what it was really like to pound hot metal all day, every day, in the heart of the Middle Ages?

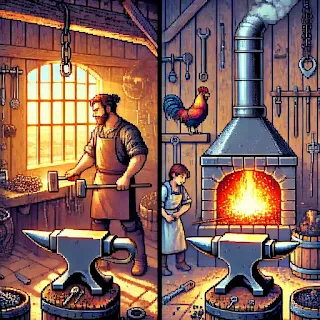

Forget the romanticized images of strong, silent men crafting intricate swords with ease.

The reality of a medieval blacksmith's life was far more gritty, demanding, and utterly fascinating.

It was a life defined by sweat, soot, and the constant roar of the forge, a world away from our comfortable, climate-controlled existences.

And let me tell you, it wasn't for the faint of heart.

As someone who’s spent countless hours digging into historical records, visiting reconstructed villages, and even swinging a hammer or two in a modern forge (though thankfully with far better safety gear!), I can assure you that the daily grind of a medieval blacksmith was a monumental task.

They weren’t just artisans; they were the backbone of their communities, indispensable to warfare, agriculture, and daily survival.

So, grab a hypothetical ale, pull up a stool (far from the sparks, trust me), and let's journey back in time.

We're about to uncover the unvarnished truth about what it took to be a master of metal in an age when iron was king.

You might be surprised by just how tough, ingenious, and utterly vital these unsung heroes truly were.

---Table of Contents

- The Early Start: When the Forge Awakens

- The Tools of the Trade: More Than Just a Hammer

- Mastering the Fire: The Heart of the Forge

- A Day in the Life: From Ploughshares to Swords

- The Physical Toll: A Body Forged in Fire

- Community and Commerce: Beyond the Anvil

- The Blacksmith's Legacy: Shaping the Medieval World

- Beyond the Daily Grind: Innovation and Artistry

- The Unsung Heroes: Why Their Story Matters

The Early Start: When the Forge Awakens

Imagine this: it's still dark, the air is crisp, maybe a bit damp.

The rooster hasn't even had his first proper crow, and you're already stirring.

For a medieval blacksmith, the day didn’t begin with a leisurely cup of coffee and a scroll through social media, believe me.

No, their alarm clock was the rising sun (or often, well before it), and their morning ritual involved a brisk walk to a cold, dark forge.

Think about it: no electricity, no easy way to get things going with the flick of a switch.

The first order of business was almost always getting the forge fire lit.

This wasn't a quick process.

You'd need good kindling, carefully stacked charcoal (which they often had to make themselves or procure through trade), and a good deal of puffing on the bellows to get that initial spark to catch and grow into a roaring inferno.

It was a bit like trying to start a stubborn campfire every single morning, except your livelihood depended on it.

And let me tell you, the quality of your fire dictated the quality of your work.

Too cold, and the metal wouldn’t shape properly.

Too hot, and you’d risk burning the steel, making it brittle and useless.

This initial period, often an hour or more before any actual hammering began, was crucial.

It was a time for quiet preparation, a mental warm-up before the physical demands truly kicked in.

They’d be assessing the day’s tasks, perhaps mentally running through the repairs needed on a broken ploughshare or picturing the steps for forging a new axe head.

There was no room for error, no quick fixes if you got off on the wrong foot.

The whole village might be relying on your ability to fix their tools or create new ones, so getting the forge ready was a serious business.

It was a testament to their discipline and dedication, rising before the rest of the world to bring the heart of their trade to life.

And the smell of that woodsmoke and burning charcoal, mixing with the damp morning air? That was the blacksmith’s perfume, a sign that the workshop was alive and ready for another day of transformative labor.

---The Tools of the Trade: More Than Just a Hammer

When you picture a medieval blacksmith, what's the first tool that comes to mind?

Probably a hammer, right?

And you wouldn't be wrong; the hammer was undeniably king in the forge.

But to truly understand their daily life, you need to appreciate the entire arsenal they wielded, often crafted by their own hands.

It wasn't just about brute force; it was about precision, leverage, and understanding the properties of metal.

First, there's the **anvil**, that massive, silent partner.

It’s not just a block of metal; it’s carefully shaped, with a flat face for general hammering, a horn for bending and shaping curves, and a hardy hole for various tools.

A good anvil was a blacksmith's most prized possession, often passed down through generations, bearing the marks of countless blows.

Then came the variety of **hammers** themselves.

They weren’t one-size-fits-all.

You’d have heavy sledgehammers for initial shaping, lighter cross-peen and straight-peen hammers for drawing out and spreading metal, and even specialized hammers for specific tasks like riveting or planishing (smoothing surfaces).

Each had its purpose, and a skilled blacksmith knew exactly which one to reach for without a second thought.

Next up, the **tongs**.

These were absolutely vital for holding the scorching hot metal.

Imagine trying to work with a piece of iron glowing cherry red – you can’t just pick it up!

Blacksmiths would have a diverse collection of tongs: flat-jawed tongs, bolt tongs, box tongs, each designed to securely grip different shapes and sizes of metal.

Making a new pair of tongs for a specific job was a common task for them, a testament to their self-reliance.

Beyond these mainstays, there were **punches** for making holes, **chisels** for cutting hot and cold metal, **swages** and **fullers** for shaping and detailing, and various other specialized tools that might only see use for particular projects.

And let’s not forget the **bellows** – those magnificent, tireless lungs of the forge, keeping the fire alive and hot enough to work the metal.

Operating them effectively required skill and rhythm, often a job for an apprentice or a younger family member, ensuring a consistent blast of air to the coals.

Each tool was an extension of the blacksmith's will, honed and perfected over years of trial and error.

They weren't just objects; they were partners in creation, allowing the blacksmith to transform raw material into the essential items that kept medieval society functioning.

It's a stark reminder that even without advanced machinery, incredible craftsmanship was possible with the right knowledge and a well-curated set of tools.

---Mastering the Fire: The Heart of the Forge

If the anvil was the blacksmith’s solid foundation and the hammer their voice, then the fire was undeniably their very breath, the pulsing heart of the forge.

And let me tell you, managing that fire wasn't just about keeping it lit; it was a nuanced, critical skill that separated the true masters from the apprentices.

Think of it like this: a modern chef controls the heat of an oven or stove with precise dials and digital readouts.

A medieval blacksmith had no such luxuries.

Their control mechanisms were far more primitive, yet their understanding of heat and its effect on metal was profound, born from countless hours of observation and experience.

The primary fuel, as I mentioned, was usually **charcoal**.

Why charcoal? Because it burns hotter and cleaner than wood, producing less ash and more consistent heat, which is absolutely vital when you're trying to forge metal.

But even with charcoal, the trick was getting the metal to the *exact right temperature* for the specific task at hand.

If the iron or steel wasn't hot enough, it would resist shaping, potentially cracking or leading to a poorly formed product.

If it was too hot, it could "burn" – essentially, the carbon would oxidize out of the steel, making it brittle and useless, like overcooked meat that's turned to charcoal itself.

This temperature control was achieved mainly through the use of the **bellows**.

By pumping the bellows, the blacksmith (or their assistant) would force more air into the heart of the fire, increasing the oxygen supply and making the coals burn hotter and brighter.

Reducing the air flow would cool it down.

It was a constant dance: observe the color of the metal, listen to the hiss and crackle of the coals, feel the heat radiating, and adjust the bellows accordingly.

And what about the **colors**?

Oh, the colors were everything!

A dull red might be good for rough bending, a bright cherry red for general forging, an orange or even yellowish white for welding different pieces of metal together.

Experienced blacksmiths could tell the exact temperature of a piece of metal just by looking at its glow, even in the dim light of the forge.

It was an art form in itself, a silent conversation between the artisan and the element of fire.

Moreover, the setup of the forge itself mattered.

The shape of the firepot, the placement of the tuyere (the pipe delivering air from the bellows), and the method of banking the coals all contributed to the effectiveness and efficiency of the heat.

This wasn't just about muscle; it was about deeply understanding metallurgy long before the science of it was formally established.

Mastering the fire meant mastering the very essence of their craft, allowing them to transform stubborn raw material into pliable, workable iron and steel.

It was a skill born from intuition, observation, and an undeniable respect for the raw power they harnessed every single day.

For more on medieval tools and techniques, you might find this resource from the New England Blacksmiths interesting:

Explore Medieval Forging Techniques

---A Day in the Life: From Ploughshares to Swords

So, the forge is roaring, the tools are ready, and the blacksmith is fueled by a hearty (if simple) breakfast.

What exactly filled the hours of their working day?

Well, their "to-do" list was incredibly diverse, reflecting the central role they played in medieval society.

There was no specialization like we see in modern manufacturing; a medieval blacksmith was a jack-of-all-trades, a one-person factory for almost everything made of metal.

The bulk of their work was often mundane, yet absolutely critical: **agricultural tools**.

Think about it: in a time when most people lived off the land, a broken ploughshare could mean a ruined harvest, and a dull scythe could halt vital haymaking.

So, a significant portion of the blacksmith's day was spent repairing and maintaining these essential items.

Sharpening axes and adzes, mending broken hoes, re-pointing ploughshares – these were the bread and butter jobs, ensuring the community could feed itself.

Then there were **household items**.

Latch mechanisms for doors, hinges that creaked but held firm, fireplace tools, cooking utensils, even simple nails – these were all handcrafted in the forge.

Every piece unique, bearing the marks of the smith's individual hammer blows.

And let's not forget the constant need for **fasteners**.

Nails were not mass-produced; each one was painstakingly forged, cut, and headed by hand.

Imagine the sheer volume of nails needed for building a house, a barn, or even a simple fence!

This mundane, repetitive task was crucial to construction.

But it wasn't all about utility.

The blacksmith also turned their hand to more specialized tasks, though perhaps less frequently.

**Weaponry and armor repair** would certainly come up, especially during times of conflict.

A knight's sword might need re-honing, a chainmail shirt might need new rings, or a spearhead might need to be forged.

These were high-stakes jobs, requiring immense skill and precision, as lives could depend on the quality of their work.

Sometimes, they even dabbled in **artistic or decorative ironwork**, especially for churches or the homes of wealthy patrons.

Intricate gates, ornate hinges, or decorative wall sconces – these showcased the blacksmith’s mastery beyond mere function, adding beauty to the otherwise stark medieval landscape.

A typical day might involve starting with a few hours on urgent repairs, then perhaps moving on to a larger project like forging a new wagon wheel band, interspersed with smaller jobs like making a dozen nails or sharpening a knife brought in by a villager.

The rhythm was constant: heat, hammer, cool, repeat.

The clanging of the hammer on the anvil was the soundtrack of the village, a comforting sign that things were being made, repaired, and the world kept turning.

For some captivating visuals of how a smith works, you can check out this resource from the Victoria and Albert Museum:

---The Physical Toll: A Body Forged in Fire

Let's be blunt: being a medieval blacksmith was back-breaking, lung-filling, and skin-blistering work.

This wasn't a desk job, folks.

It was an incredibly physical profession that demanded immense strength, stamina, and resilience.

Imagine swinging a heavy hammer, hour after hour, day after day.

Your arms, shoulders, and back would develop an incredible musculature, but they’d also be constantly aching.

The repetitive motions, the sheer force required to shape iron, took a tremendous toll on the joints and muscles.

It's no wonder many blacksmiths developed distinct physical characteristics, often broad-shouldered and powerfully built.

Then there's the **heat**.

Oh, the relentless, oppressive heat!

Working mere feet from a roaring forge, surrounded by glowing hot metal, in a poorly ventilated (or entirely unventilated) workshop, meant constant exposure to extreme temperatures.

Dehydration was a serious concern, and heatstroke was a very real danger, especially in the summer months.

Sweat would pour, blurring vision and making everything slippery.

And the **smoke and fumes**?

Charcoal smoke contains carbon monoxide, and heating certain metals could release other noxious fumes.

Without modern ventilation systems, blacksmiths were constantly inhaling these particles and gases.

This undoubtedly led to chronic respiratory problems, coughs, and a shortened lifespan.

The air in a medieval forge was thick with the smells of burning fuel and hot metal, but also with invisible hazards.

And let's not forget the **risks of the trade** itself.

Sparks were a constant hazard, ready to burn skin or clothing.

Hot scale (bits of oxidized metal) flying off the workpiece could cause painful injuries.

A missed hammer blow could result in a smashed finger or worse.

The sheer weight of the tools and the metal being worked meant that a dropped item could cause serious injury.

Eye injuries from flying debris were probably common, leading to impaired vision later in life.

There were no safety glasses, no steel-toed boots, no protective gloves beyond simple leather.

The blacksmith's body was literally their first and only line of defense.

It’s easy to romanticize the craft, but the reality was a life of discomfort, pain, and constant physical strain.

Yet, they endured.

They endured because their skills were vital, because their families depended on them, and perhaps because there was an undeniable satisfaction in taking raw, unyielding material and bending it to their will, creating something useful and lasting with their own hands.

Their bodies were testaments to their dedication, hammered and shaped almost as much as the iron they worked.

---Community and Commerce: Beyond the Anvil

While the image of a lone blacksmith toiling away in a secluded forge is powerful, the reality was that they were deeply integrated into the fabric of medieval community and commerce.

Their forge was often a hub of activity, a place where villagers gathered, gossiped, and conducted business.

Think of it as the medieval equivalent of a general store and repair shop rolled into one, with the added entertainment of sparks flying!

Economically, the blacksmith was indispensable.

They operated on a mixture of custom orders, repairs, and perhaps even some speculative work (making nails or common tools to have on hand).

Payment wasn't always in coin; bartering was incredibly common.

A farmer might pay for a repaired ploughshare with a portion of his harvest, a shepherd with wool or a lamb, and so on.

This meant the blacksmith had to be not only a skilled artisan but also a savvy businessman, managing supplies, accounting for various forms of payment, and maintaining good relationships with their customers.

Their reputation was everything.

A blacksmith known for shoddy work or unfair prices wouldn't last long in a close-knit community.

Conversely, a skilled and honest smith would be highly respected and sought after, often serving multiple villages or even the local lord.

They were often trusted figures, privy to the comings and goings of the village, and perhaps even a source of news or gossip as people waited for their items to be fixed.

Beyond the practical, blacksmiths sometimes held a special, almost mystical status.

Working with fire and transforming raw earth (iron ore) into useful objects could seem like magic to some, especially in a superstitious age.

They were seen as masters of powerful elements, and some folklore even associated them with supernatural abilities.

This blend of practicality and perceived power meant they occupied a unique place in medieval society.

They weren’t isolated craftspeople; they were integral parts of the social and economic machinery, vital to the survival and prosperity of their communities.

Their success was intertwined with the success of the village, making their daily efforts all the more significant.

To learn more about the economic life of medieval commoners, you might find this article interesting:

Understanding Medieval Economies

---The Blacksmith's Legacy: Shaping the Medieval World

It's easy to look back at the Middle Ages and focus on knights, castles, and kings.

But quietly, in the smoky confines of their forges, blacksmiths were shaping the very world around them, often with more direct and tangible impact on daily life than any monarch.

Their legacy isn't just in the rusty artifacts dug up by archaeologists; it's woven into the very fabric of how medieval society functioned and evolved.

Consider the **agricultural revolution** of the Middle Ages.

Improvements in farming techniques, like the heavy plough and horse collar, were only possible because blacksmiths could forge the necessary iron components.

More efficient farming meant more food, which in turn supported a larger population and the growth of towns.

Without the smith, these advancements would have been impossible.

Then there's the **military impact**.

From the humblest arrowheads to the most intricate pieces of plate armor, weapons and defenses were the products of the forge.

The strength and quality of a knight's sword or the integrity of a castle's iron-bound gates could literally determine the outcome of battles and sieges.

Blacksmiths were, in essence, the arms manufacturers of their era, vital to defense and conquest.

Beyond that, think about **construction**.

Every wooden structure, from peasant cottages to grand cathedrals, relied on nails, hinges, and iron straps forged by hand.

The blacksmith provided the essential "glue" that held the physical world of the Middle Ages together.

Their skill was also crucial for **transportation**.

The iron tires of wagon wheels, the shoes for horses and oxen – these were all vital for trade, travel, and warfare, and they all came from the forge.

A broken wheel could strand a merchant, and a thrown shoe could cripple a warhorse.

What's truly remarkable is that this immense impact was achieved through sheer grit, ingenuity, and a deep understanding of materials, largely without formal scientific training.

They learned through apprenticeship, observation, and painstaking trial and error, passing down knowledge from one generation to the next.

The very name "Smith" (and its variations in other languages) being one of the most common surnames globally speaks volumes about their pervasive influence.

It's a direct echo of their foundational role in society.

So, the next time you see a rusty old horseshoe or a medieval tool in a museum, remember the hands that hammered it into being.

Remember the sweat, the heat, the dedication, and the undeniable impact of the medieval blacksmith.

They were the true unsung architects of the world we've come to know, their legacy forged in fire and enduring through the ages.

---Beyond the Daily Grind: Innovation and Artistry

While a significant portion of a medieval blacksmith's day was filled with the utilitarian and the repetitive, it would be a mistake to see them as mere automatons of the anvil.

Oh no, there was a profound current of innovation and artistry running through their veins, often born out of necessity, but just as often driven by a desire for excellence.

Think about the sheer ingenuity involved in problem-solving.

A farmer brings in a tool broken in a completely new way, or a lord commissions a gate with an unfamiliar design.

The blacksmith couldn't just look up a YouTube tutorial or order a specialized part online.

They had to invent, adapt, and refine their techniques on the fly, relying on their deep understanding of metal and their own creative minds.

This constant need for adaptation fostered a quiet but relentless pace of **innovation**.

Improvements in forge design, more efficient bellows, new methods of joining metals, or better ways to temper steel – these weren't discovered in laboratories, but through the dirty, hands-on experimentation of countless smiths over centuries.

Each small refinement added up, contributing to the slow but steady technological progress of the age.

And then there's the **artistry**.

While many pieces were purely functional, many others transcended mere utility.

Consider the ornate ironwork seen on medieval cathedrals, the intricate patterns sometimes found on sword blades (like pattern welding, a highly complex technique), or the delicate scrollwork on a wealthy patron's chest hinges.

These weren't just hammered out; they were carefully designed, shaped with precision, and often adorned with decorative elements that speak to a profound aesthetic sensibility.

It was a testament to the fact that even in a harsh, practical world, there was still room for beauty and craftsmanship.

A master blacksmith wasn't just someone who could hit metal hard; they were someone who understood its potential, who could coax intricate forms from stubborn iron, and who could imbue their creations with a sense of grace and strength.

This blend of practicality and artistry is what makes the blacksmith's craft so enduringly fascinating.

They were the engineers and artists of their time, solving the problems of the day while simultaneously leaving behind a legacy of durable beauty.

Their daily grind was punctuated by moments of intense creativity, pushing the boundaries of what was possible with fire, hammer, and anvil.

It's a good reminder that true innovation often comes from those closest to the material, working with their hands and their wits.

For more about the history of metalworking artistry, this might be a good starting point:

---The Unsung Heroes: Why Their Story Matters

We've delved deep into the smoky, clangorous world of the medieval blacksmith, exploring their early starts, their essential tools, their mastery of fire, and the diverse demands of their day.

We've even touched upon the tremendous physical toll their profession took and their vital role in the community and economy.

But why does the story of these medieval artisans matter so much to us today?

Why should we care about the daily grind of someone who lived a thousand years ago?

Well, for one, it's a powerful reminder of the **foundational nature of craftsmanship**.

In our modern world of mass production and disposable goods, it’s easy to forget the value of something made by hand, with skill, dedication, and an understanding of materials.

The blacksmith embodies that spirit of creation, of transforming raw resources into something useful and lasting.

Their story also highlights the **resilience and ingenuity of humanity**.

Facing harsh conditions, limited technology, and constant demand, these individuals didn't just survive; they innovated, adapted, and built the very infrastructure of their world.

They teach us about problem-solving through practical application, a skill just as valuable today as it was then.

Furthermore, understanding the blacksmith's daily life gives us a deeper appreciation for the **interconnectedness of medieval society**.

No knight could ride without a blacksmith to shoe his horse; no farmer could plough without a smith to maintain his tools.

Every piece of progress, every daily activity, was reliant on the skilled hands of these metalworkers.

They were, in many ways, the engineers and technicians of their time, making everything else possible.

And finally, for me, there's a certain **romance in the grit**.

It's easy to admire the grand gestures of history, but the daily, persistent effort of ordinary people is what truly built the world.

The blacksmith, covered in soot, deafened by the hammer, yet tirelessly shaping metal, represents that enduring human spirit – the desire to create, to fix, to contribute, and to leave a mark.

So, the next time you hear a distant clang, or see a piece of old ironwork, take a moment to remember the medieval blacksmith.

They were more than just workers; they were artists, engineers, and indispensable pillars of their communities, whose fiery dedication shaped an entire era.

Their daily life, though arduous, was a testament to the power of human skill and perseverance, a story that absolutely deserves to be remembered and celebrated.

Medieval Blacksmith, Forge, Anvil, Ironwork, Daily Life

📖 Read: 3 Forgotten Women Who Secretly Shaped History